What is Vaccine Beer

Vac beer contains live yeast cells that produce harmless viral proteins. It’s a new food product that can elicit antibody responses against viruses.

I’ve homebrewed beer off and on for 30 years. When I saw that feeding lab mice with engineered brewer’s yeast could induce protective antibody responses against the virus I study, my instant first thought was, “well, I can definitely do that at home.”

In this post, I’m mirroring the independent manuscript my brother and I wrote describing our home experiments. There’s also an institutional manuscript showing that drinking beer made with vaccine yeast induced a strong antibody response in me. Tina Saey’s excellent coverage of the controversies surrounding the new tech can be found here.

In the near future, I hope to convince major brewing yeast suppliers to start offering “vac yeast” for microbrewers and homebrewers to play with. While we wait for that to happen, it’s already possible for independent scientists to try all this stuff at home, exactly like I did.

The Supplemental section of the posted manuscript contains a wealth of technical detail about our methods for homebrewing and drinking vac beer. Unfortunately, the detailed methods too long for the blogging platforms, so I’ll simply direct interested readers to the Zenodo posting.

The appendices of the home experiment manuscript are given separate coverage here and here.

Vaccine Beer: A Personal Healthcare Report

Christopher B. Buck1 and Andrew R. Buck2

1Independent Scientist, Bethesda, Maryland, USA

2Independent Scientist, Vallejo, California, USA

Abstract

Recent results publicly presented by the National Cancer Institute suggest that live yeast expressing vaccine antigens can immunize mice when delivered in the form of food. In this study, we set out to test the hypothesis that a food-based vaccine approach can be independently implemented in a home kitchen outfitted with a few thousand dollars worth of scientific equipment. Commercial brewer’s yeast were engineered to express the BK polyomavirus major capsid protein as a model vaccine antigen. The yeast were then used to homebrew beer. Drinking prime and boost doses of the beer did not cause any discernible adverse effects. The results demonstrate that food manufacturers and home cooks can safely begin to explore the development of low-cost edible vaccines.

Introduction

Findings from a team at the National Cancer Institute (NCI) show that live brewer’s yeast expressing vaccine antigens can be immunogenic when fed to lab mice (Buck, 2025). Food-based vaccine approaches could dramatically accelerate vaccine development, lower production costs, and improve accessibility.

In this report, we explore the hypothesis that food-based vaccine strategies can safely be extended to humans by conducting pilot self-experiments in which we ate food-grade yeast expressing a model vaccine antigen. We aim for this to be the beginning of a movement to democratize vaccine development by making it approachable for food manufacturers and home cooks (Jain, 2025; Kraushaar, 2024; Mastroianni, 2023).

To explore the live yeast vaccine approach, we ordered and recombined synthetic DNA fragments to independently generate the yeast expression plasmids described by the NCI team in a home kitchen setting. Transformed yeast were then used to produce beer containing a candidate vaccine antigen, the BK polyomavirus (BKV) major capsid protein VP1. We then drank beer containing suspended live yeast. A complete lack of significant side effects supports a self-attestation that vaccine beer qualifies for generally recognized as safe status.

BKV is a known cause of kidney, bladder, brain, and cardiovascular diseases (Lee et al., 2019; Petrogiannis-Haliotis et al., 2001; Pinto & Dobson, 2014; Robles et al., 2020; Sandler et al., 1997; Starrett et al., 2023). The aim of the self-treatments presented in this report is to reduce our individual risks of developing BKV-induced disease. The study should be viewed as an autonomous self-healthcare activity (Beauchamp & Childress, 1979).

Evaluation of the possible medical efficacy of food-based vaccine strategies will be an important future aim that can be conducted under FDA supervision. Meanwhile, food producers and consumers are free to immediately begin experimenting with the technology as a self-care tool.

Materials and Methods

Ethics statement. In our view, scientific self-experimentation in service of individual healthcare is a fundamental human right (Buck, 2022; C. B. Buck, 2023). Our viewpoint rests on a long tradition of scientists initially testing research findings on themselves and is supported by the Nuremberg Code, which explicitly allows for the possibility of ethical self-experimentation (Hanley et al., 2019; Sills et al., 2020). This report documents individual self-healthcare activities that are insufficiently systematic or generalizable to meet the specialized legal definition of human subjects research. Detailed reasoning on this issue is presented in Appendix A.

The independent generation, consumption, and sale of genetically modified organisms (GMOs) is allowed under US law (Kramer, 2023). In our view, the GMO yeast described in this report meet federal Generally Recognized as Safe (GRAS) food standards. Detailed reasoning on this issue is presented in Appendix B.

The personal healthcare activities documented in this report did not use any confidential information, did not use or generate any intellectual property, and did not receive or use any government resources. The self-treatments were conducted in a home environment outside of work hours and do not in any way invoke our professional titles. The report does endorse any persons, entities, or products.

Plasmid construction. The sequence of pGustiv was downloaded from the Lab of Cellular Oncology’s public technical page. The sequence was synthesized as a set of cloned fragments by GeneUniversal.com. Fragments were recombined in a home lab setting using traditional restriction enzyme-based cloning methods (NEB.com). Scientific equipment was purchased from The-Odin.com or via Amazon.com. The finished pGustiv plasmid is publicly available for any purpose, including human studies or commercial products, under OpenMTA (Kahl et al., 2018) via Addgene.org. We note that various companies, including Gene Universal, offer custom cloning services that would obviate the need for home laboratory equipment.

Yeast transformation. Detailed methods for transforming yeast and producing beer are provided in the Supplemental Methods section. In addition, we note that many companies, including Gene Universal, offer yeast transformation services.

Yeast strains of interest were transformed with pGustiv using a yeast transformation kit (The-Odin.com) and selected on YPD-agar plates (KDmedical.com) with 6 mM formaldehyde (SigmaAldrich.com). Six colonies were pooled into liquid YPD with 6 mM formaldehyde (YPD-6) and cultured with orbital shaking at 30ºC for several hours prior to streaking onto malt extract plates (OlympusMyco.com). Six of the largest and most fluorescent colonies were picked into 250 µl of YPD-6 and cultured overnight. The culture was then progressively stepped up to 25 mL and 250 mL of YPD-6 in stirred Erlenmeyer flasks. Sedimented stationary phase cells from the 250 mL culture are considered a salable unit suitable for production of up to five gallons of vaccine beer.

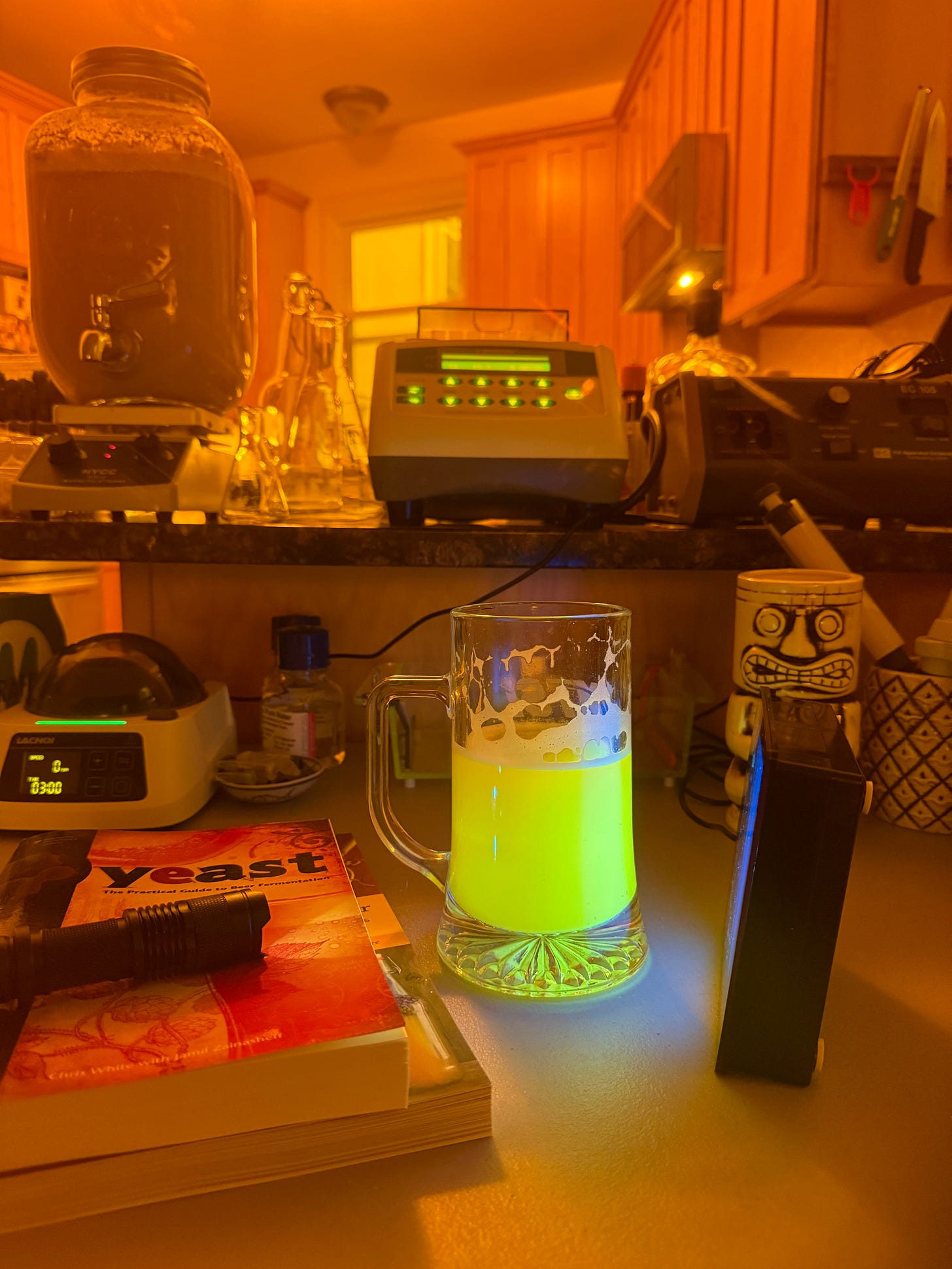

Beer. Uninduced yeast transformed with pGustiv were cultured to near opacity in 250 mL of YPD-6 culture broth in a stirred Erlenmeyer flask. The cells were then spun down and the YPD-6 supernatant was discarded. Collected yeast cells were pitched into one liter (~one quart) of 1x Propper starter broth (OmegaYeast.com) in a 5-liter (~one gallon) continuous brewing jar (CulturesForHealth.com). The starter was cultured with stirring until expression of the green fluorescent protein (GFP) marker gene started to become evident, roughly 6-12 hours. Three liters (~3 quarts) of filtered tap water and 0.5 kg (~1 pound) of dry malt extract from a MoreBeer.com Flash Hefeweizen kit were added to the fermenter. Thirty grams (~1 ounce) of Saphir hop pellets (Artisan Hops) were steeped in a French press (Frieling) in 0.5 L (~1 pint) of boiling water. The hop tea was cooled and pressed and the filtrate was added to the fermenter. Fermentation was conducted at 24 to 34ºC (75-93ºF), depending on yeast strain. The home kitchen environment did not have the resources to quantitate VP1 dosing, but a rough estimate would be that, indexed to body mass, author CBB consumed roughly 1/38th of a mouse dose of induced live yeast during each roughly five-day dosing window.

Self-treatments. Both authors conducted pilot self-treatments by consuming beer on an arbitrary “best guess” convenience schedule consisting of one or two pints of beer per day.

Robust GFP expression was observed in the fermenting beer starting roughly 36 hours after pitching, at which point a pint of fresh beer with suspended live yeast was decanted from the stirred fermenter and immediately consumed at fermentation temperature. At day 3 of the fermentation, the remaining beer was distributed into one-pint flip-top bottles and carbonated by the addition of 1% (w/v) maltose (LabAlley.com).

A 20 mg dose of famotidine was taken about an hour in advance of some pints, in hopes of partially neutralizing stomach pH to promote the survival of live yeast. Sugar-free calcium carbonate antacid tablets were chewed alongside some meals, with the same rationale. Some pints were consumed on an empty stomach, while others were consumed alongside maltose-rich foods, in hopes of achieving prebiotic yeast-feeding effects (see Supplemental Methods Section B). Some of the pints were consumed together with a high-fat meal, exploring the hypothesis that the secretion of bile salts might help promote yeast lysis and release of BKV VLPs in the duodenum. In summary, the prime and boost dosing schedules consisted of one or two pints of vaccine beer per day over the course of about five days.

Results

The traditional Uniform Biological Material Transfer Agreement (UBMTA) used by the NCI team stipulates that transferred materials cannot be used in human subjects. The UBMTA also forbids further sharing or resale of transferred materials. It was therefore necessary to independently recreate the pGustiv plasmid through commercial DNA synthesis. Plasmid construction was conducted in the home kitchen of author CBB (Chris). The finished plasmid is freely available via Addgene under OpenMTA, which allows for use in humans and commercial resale (Kahl et al., 2018).

The pGustiv plasmid was initially transformed into Pakruojis Lithuanian Farmhouse Ale Yeast (White Labs WLP4047) in the home lab setting. Detailed methods are provided in the Supplemental Methods section. The transformed yeast strain was used to brew batches of roughly a gallon (4 L) of beer. Chris drank one or two pints (0.5-1 L) of the resulting vaccine beer per day over the course of about a week (Figure 1).

The wheat ale yeast strain (Fermentis WB-06) that comes with the Morebeer Flash Hefeweizen kit also produces a flavorful live-yeast beer. Results from the NCI team suggest that the wheat ale strain may exhibit somewhat higher and more stable vaccine antigen expression than the Pakruojis strain. Chris drank booster doses of vaccine beer made with the wheat ale strain starting at roughly week seven after the Pakruojis priming doses. A second round of booster doses using WB-06 beer was produced using the Simplified Beer Production protocol (Supplemental Methods Section A). Author ARB (Andrew) also produced and gradually consumed a gallon of beer produced using wheat ale yeast carrying pGustiv.

The NCI team’s vaccination experiments with mice suggest that it’s important for live yeast to shuttle the fragile vaccine antigen past the stomach acid barrier. We suspect it’s also important for the yeast cells to eventually break open and release the antigen so it can directly bind the surface of specialized immune presentation cells called M cells in the small intestine (de Aizpurua & Russell-Jones, 1988). We have entertained multiple hypotheses about which foods might be most effective for facilitating these processes. We don’t know which, if any, of the hypotheses are true, and some of the hypotheses are mutually exclusive. We adopted a bet-hedging strategy in which we implemented different strategies on different days (see Supplemental Methods Section B).

In healthy individuals, yeast can persist in the gut for periods of up to a few days (Pecquet et al., 1991). One hypothesis is that it might be possible to restimulate antigen expression in yeast residing in the small intestine. The MAL32 promoter system used in pGustiv is activated by maltose, so eating maltose-rich foods might restimulate antigen expression. A complicating factor is that glucose suppresses the MAL32 promoter, even in the presence of high levels of maltose. In essence, yeast cells are set up to utilize glucose as a preferred “snack food” before they activate the machinery to metabolize other sugars, such as maltose.

In pilot self-experiments, eating low-glucose/maltose-rich foods alongside vaccine beer sometimes correlated with mild bloating and flatulence, reminiscent of the familiar effects of eating beans. We also considered the hypothesis that gut fermentation might produce ethanol at levels that could produce intoxicating effects beyond what might be expected from drinking a pint of beer. We did not sense any signs of unexpected ethanol intoxication during the experiments. No other discernible side effects were detected at any point during or after the experiments.

Discussion

In terms of lives saved, vaccines have been among the most important public health interventions in human history (Berkley, 2025). Expansion of our collective vaccine arsenal to cover additional pathogens would undoubtedly save millions more lives and further avert a mountain of human misery. It is critical that we find ways to make vaccine development faster, easier, cheaper, and more broadly accessible. Food-based vaccine approaches can achieve these goals.

In the United States, there has been a growing movement to downplay the safety and efficacy of traditional vaccines, and government officials have recently begun implementing policies restricting access (O’Reilly, 2025). Food-based vaccines could help put autonomous decision-making authority back in the hands of individual Americans. Homemade vaccines might also help overcome some of the skepticism and fear surrounding traditional injected vaccines developed by pharmaceutical conglomerates.

While considering the legal requirements for IRB pre-approval (Appendix A) we reviewed a 1948 publication discussing Stanford University’s policy of withholding treatment from older adults with latent syphilis (Blum & Barnett, 1948). The rationale for the policy was that the value of penicillin for treating latent syphilis hadn’t yet been conclusively proven. Armed with the hindsight knowledge that penicillin is safe and effective for treating latent syphilis, one could argue that Stanford’s medical withholding policy inadvertently caused the deaths of dozens of syphilis patients. A more modern example of the medical withholding problem is a policy that denied shingles vaccines to people born prior to an arbitrary birth date (Taquet et al., 2024). The randomized natural experiment revealed that people who were denied the shingles vaccine suffered increased risk of developing dementia. We should strive to avoid repeating this type of error (C. Buck, 2023a, 2023b). While the research community is pursuing conclusive proof of medical efficacy, people should be allowed to decide which medical cost/risk/benefit balance is right for them, as individuals (C. B. Buck, 2023).

The existing regulatory framework in the US empowers food producers to sell innovative new foods. There have been recent “rulemaking” proposals under which regulators would override statutory language and require laborious government pre-approval processes for any new food innovation (Harrison et al., 2025; Makary, 2025). These proposals would strip consumers of their right to buy potentially healthy foods.

Current law supports a path in which food-based vaccine development could be simplified to the point that free market forces, combined with standard scientific scrutiny, could serve as a check-and-balance against regulatory overreach (Buck, 2024a, 2024b). It could be helpful for the research community, including independent scientists, to begin exploring the question of whether results with BKV can be extended to edible vaccines covering emerging threats, such as H5N1 influenza or current SARS-CoV-2 variants.

Colleagues have expressed the concern that because vaccines are typically considered drugs, they should only be developed under the authority of the FDA drug approval process. This concern overlooks the fact that many foods are known to have drug-like medicinal properties, but the existence of medicinal properties doesn’t make a food a drug unless the manufacturer makes claims to that effect. It might help to consider an analogy. When Chris’s 23andMe results indicated that he has polymorphisms associated with risk of macular degeneration, he became interested in scientific literature suggesting that a GRAS food ingredient called zeaxanthin might help mitigate the possible risk. He was impressed when his ophthalmologist advised him to consider eating zeaxanthin-rich foods, such as spinach. There was even a brief discussion concerning which cooking methods seem most likely to increase zeaxanthin bioavailability. Chris may or may not be at actual risk of macular degeneration - and spinach may or may not be an effective treatment - but that doesn’t mean the ophthalmologist was reckless to recommend it. It also doesn’t mean Chris must file an IRB proposal or an Investigational New Drug application before growing spinach for his family, and it doesn’t mean supermarkets should consider moving spinach to the pharmaceutical aisle. Extending the thought experiment, a new strain of spinach engineered to produce extra zeaxanthin could still be marketed as a food - so long as there aren’t label claims about prevention of macular degeneration or other diseases. The point of the analogy is that vaccine beer, like spinach, can immediately be marketed as a potentially healthful food in full compliance with federal law.

The ophthalmologist is right. People should be empowered to exercise their right to self-experiment with healthy foods (Buck, 2022).

References

1. Buck, C. How to Make and Share Vaccine-Style Beer. in World Vaccine Congress. 2025. Washington, DC.

2. Mastroianni, A. Let’s build a fleet and change the world. Experimental History, 2023.

3. Jain, H. Cottage-Core Biotech. Mundane Beauty, 2025.

4. Kraushaar, L. Individualised Lifestyle Medicine — The FDA-Approved N-Of-1 Method To Test Drive Health Advice. Read or Die, 2024.

5. Pinto, M. and S. Dobson, BK and JC virus: a review. J Infect, 2014. 68 Suppl 1: p. S2-8.

6. Starrett, G.J., et al., Evidence for virus-mediated oncogenesis in bladder cancers arising in solid organ transplant recipients. Elife, 2023. 12.

7. Robles, M.T.S., et al., Analysis of viruses present in urine from patients with interstitial cystitis. Virus Genes, 2020. 56(4): p. 430-438.

8. Sandler, E.S., et al., BK papova virus pneumonia following hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant, 1997. 20(2): p. 163-5.

9. Petrogiannis-Haliotis, T., et al., BK-related polyomavirus vasculopathy in a renal-transplant recipient. N Engl J Med, 2001. 345(17): p. 1250-5.

10. Lee, Y., Y.J. Kim, and H. Cho, BK virus nephropathy and multiorgan involvement in a child with heart transplantation. Clin Nephrol, 2019. 91(2): p. 107-113.

11. Beauchamp, T.L. and J.F. Childress, Principles of Biomedical Ethics. 1st ed. 1979, New York: Oxford University Press.

12. Buck, C. The Freedom to Choose Medicine Is a Civil Right. Viruses Must Die, 2022.

13. Buck, C.B., The mint versus Covid hypothesis. Med Hypotheses, 2023. 173.

14. Hanley, B.P., W. Bains, and G. Church, Review of Scientific Self-Experimentation: Ethics History, Regulation, Scenarios, and Views Among Ethics Committees and Prominent Scientists. Rejuvenation Res, 2019. 22(1): p. 31-42.

15. Sills, J., P.W. Estep, and G.M. Church, Transparency is key to ethical vaccine research. Science, 2020. 370(6523): p. 1422-1423.

16. Kramer, A., The Secret Ingredient in Your Craft Beer? Gene-Edited Yeast. 2023.

17. Kahl, L., et al., Opening options for material transfer. Nat Biotechnol, 2018. 36(10): p. 923-927.

18. de Aizpurua, H.J. and G.J. Russell-Jones, Oral vaccination. Identification of classes of proteins that provoke an immune response upon oral feeding. J Exp Med, 1988. 167(2): p. 440-51.

19. Pecquet, S., et al., Kinetics of Saccharomyces cerevisiae elimination from the intestines of human volunteers and effect of this yeast on resistance to microbial colonization in gnotobiotic mice. Appl Environ Microbiol, 1991. 57(10): p. 3049-51.

20. Berkley, S., Unraveling the arc of vaccine progress. Science, 2025. 389(6763): p. eaea7053.

21. O’Reilly, K.B. Latest ACIP move is dangerous to the nation’s health. Prevention & Wellness, 2025.

22. Blum, H.L. and C.W. Barnett, Prognosis in Late Latent Syphilis. Archives of Internal Medicine, 1948. 82(4): p. 393-409.

23. Taquet, M., et al., The recombinant shingles vaccine is associated with lower risk of dementia. Nat Med, 2024. 30(10): p. 2777-2781.

24. Buck, C. Everybody Should Be Allowed to Choose the HPV Vaccine. Viruses Must Die, 2023.

25. Buck, C. We Tuskegeed My Dad. Viruses Must Die, 2023.

26. Makary, M. Statement from FDA Commissioner Marty Makary, MD, MPH: 100 Days of Embracing Gold-Standard Science, Transparency and Common Sense. 2025.

27. Harrison, T.A., C.A. Lewis, and N. Yapp FDA Announces Notice of Proposed Rulemaking to Eliminate Self-Affirmed GRAS and Revise GRAS Review Criteria. Venable, 2025.

28. Buck, C. Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Health Experiments. Viruses Must Die, 2024.

29. Buck, C. Consumer Reports for Medicines. Viruses Must Die, 2024.

Very cool, if i have some time might give this a crack but with rhinovirus VP0. Maybe conserves enough to stop some significant % of colds?

1. What is the alcohol content of vaccine beer? I'm not a home brewer but I'm guessing that the alcohol content can adjusted during the brewing process and maybe make non-alcoholic beer with yeast that produce the viral proteins?

2. What is your guess as to the minimum amount of beer to stimulate antibodies?

3. How could a minor get the health benefit from consuming yeast with viral proteins that stimulate antibody responses without consuming too much or any alcohol?

4. Any guesses on how long antibody production lasts after drinking a beer? Would antibody production fall off but come back in the event a person was exposed to the virus in the environment?

If you need to shy away from some of the questions to avoid making a health claim that's understandable. I tried to word them to give you room to maneuver but I don't live in the medico-legal world of vaccines so I may not have asked them right.

Merry Christmas.