Speculation is not a Dirty Word

We pay a steep price for pretending imagination has no place in science

A previous post celebrated the joys of constructive peer reviews. But peer review isn’t always such a bed of roses. A reviewer for our group’s recent manuscript linking bladder cancer to HPV and polyomavirus infections suggested that we remove a paragraph from the Discussion section because it was “highly speculative.” In science, there is compelling speculation and there is flimsy speculation — but too much speculation? That’s crazy-talk. Speculation is the gasoline of the scientific engine. We respectfully declined the reviewer’s suggestion, and you can now read the speculation for yourself in the final published version of the paper.

Here in Substack, I’m able to offer even more provocative speculation: it would be a good idea for everybody — of any age or gender — to get the HPV vaccine. Our data show that the vaccine realistically might reduce the risk of bladder cancer, not to mention all the other less common forms of cancer HPV has been conclusively proven to cause. A mountain of scientific evidence shows that the HPV vaccine is safe.

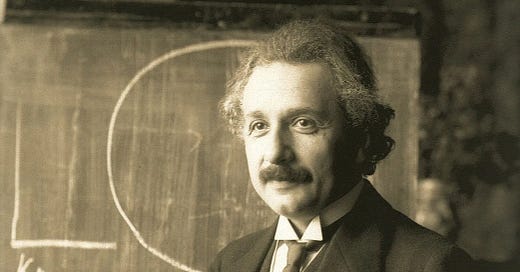

In the first season of the TV series Genius, which dramatizes the life and times of Albert Einstein, an interesting side-character is Nobel laureate and enthusiastic early-adopter of Naziism, Philipp Lenard. Throughout the narrative, Lenard intrudes to grimly intone his opinion that true Deutsche Physik is strictly an experimentalist pursuit (translation: speculation has no place in real science). Let’s go through the steps of the scientific method to see how Lenard was kind of being a nazi.

Step 1) Use intuition and imagination to identify a good question. This step is harder than it sounds. Wondering whether the Moon might be made of cream cheese obviously isn’t a very good question, but when Einstein first wondered what it might be like to ride on a beam of light that question evidently struck Lenard as similarly frivolous. Einstein speculated that it might be among the top few greatest scientific questions of all time. Genius!

Step 2) Brainstorm hypotheses and debate colleagues about which lines of speculation best account for existing observations. It’s particularly important to focus on hypotheses that provide better explanations for contradictory lines of existing evidence. In this part of the Genius storyline, Einstein speculates about possible solutions to labyrinthine equations and becomes an increasingly irritating gadfly for dogmatic authoritarians like Lenard.

Step 3) Imagine methods that could experimentally test concrete predictions. One of my favorite scenes in Genius is when Einstein and his friend Michele Besso suddenly realize that the Sun’s gravity should bend starlight in ways that would be detectable during a solar eclipse. Fortunate scientists are familiar with the addictive ecstasy of the eureka moment — but in my experience there’s also quite a lot of joy to be found in moments of “Aha! This shiny idea is actually testable!” To the extent that the eclipse epiphany scene gave me empathetic teary-eyed goosebumps.

Step 4) Solicit funding, do experiments, write manuscripts, submit claims for peer review, yada yada yada.

I yada yada yadad over the part Lenard thought of as real science for comedic effect — in reality, we can’t all be Einsteinian dreamers and somebody really does have to do the Lenardian heavy lifting of Step 4. Although even Step 4 typically has quite a bit of rinse-lather-repeat in which you’re forced to iteratively keep going back to Step 2 to generate imaginative ideas about why your experiments aren’t working the way you initially hoped they would.

In early adulthood, Einstein was repeatedly bounced away from academia by rigid entrance exams and professors who incorrectly perceived his imaginative speculation as disrespectful. Bouncing all the Einsteins away to the patent office for the supposed sin of being “highly speculative” is a terrible mistake. It could end up slowly grinding science down to an incrementalist crawl — which is exactly what appears to have been happening for the past half century.

The good news of this perspective is that we could conceivably do better without any new policies or funding. It’s possible that working scientists could move forward faster if we simply relegate Lenardian experimentalist-chauvinism to the ash heap of history and return to embracing a more Einsteinian philosophy of science. This improved philosophy could include some experimentation with unbiased grant allocation methods that might help get us out from under the incrementalist streetlight effects we seem to increasingly be stuck under.

This essay was originally posted on Medium in March 2023.